Thirty miles southeast of Las Vegas stands one of America’s most recognizable modern engineering marvels.

Hosting over a million visitors each year, this breathtaking monolithic structure has remained one of the most popular tourist destinations in the United States since its completion over 80 years ago.

For nearly three decades engineers researched the Boulder Canyon walls, testing and analyzing whether or not they would be a good home for a new dam. Not like any dam that had come before it, a new hydro-electric concrete arch-gravity dam that would provide water and electricity to millions of Americans.

The driving force behind its construction were two Republican Representatives from California, Representative Phil Swing and Senator Hiram Johnson. But critics argued that the dam’s construction would be too expensive and would mainly only benefit California.

The safety and stability of the dam project came under intense scrutiny as well. On March 12, 1928, the St. Francis Dam, an arch-gravity dam constructed by the city of Los Angeles, failed and killed 600 people.

Detractors reasoned that if this new dam project failed, every downstream Colorado River community would be destroyed.

To those who envisioned the future good the dam would bring, the benefits outweighed the risks.

On December 21, 1928, President Calvin Coolidge signed the bill authorizing the construction of the dam. The U.S. government allocated $49 million for construction costs and started accepting bids for the huge undertaking. Wouldn’t you know it, a newly formed company called Six Companies, Inc., bid $48,890,955 which was within $24,000 of what the government researchers thought the construction would cost. This would be over $660 million in current dollars.

At the time, Las Vegas was a small town of nearly 5,000 residents. After the announcement of the project the town saw nearly 20,000 unemployed workers descend on the city, desperately looking for jobs.

Construction of the Boulder Canyon dam, as it was called then, began in March 1931 with the first task being to divert the Colorado River.

To do this, four diversion tunnels were built, two on the Nevada side, two on the Arizona side. Each tunnel was 56 feet in diameter (17 meters) and nearly three miles long.

Next, two cofferdams were put in place, an upper and a lower. These cofferdams were thicker and higher than the dam itself to ensure that the river wouldn’t flood a construction site with thousands of men working. The upper cofferdam was 96 feet high and 750 feet thick.

After the construction site was drained, the workers removed the bottom of the riverbed until they found solid bedrock to lay the foundation of the dam. Nearly 1.5 million cubic yards of debris and sediment was removed and relocated.

At the same time, workers began doing the same thing to the canyon walls, removing debris and loose articles with 44-lbs jackhammers until they found solid rock which the dam would be built into and which would take the force of the water once the river pooled. These men were called “high-scalers.”

From the Bureau of Reclamation:

Their job was to climb down the canyon walls on ropes. Here they worked with jackhammers and dynamite to strip away the loose rock. The men who chose to do this work came from many backgrounds. Some were former sailors, some circus acrobats, some were American Indians. All of them were agile men, unafraid to swing out over empty space on slender ropes.

Web archive of the Bureau of Reclamation website

The most common cause of death for men in the construction zone was falling debris, but a new initiative came from these tragedies that workers still use today:

The men began making improvised hard hats for themselves by coating cloth hats with coal tar. These “hard-boiled hats” were extremely effective. Several men were hit by falling rocks so hard that their jaws were broken by the impact, yet they did not receive skull fractures. Because of these “hard-boiled hats,” men survived accidents which would otherwise have killed them. The Six Companies contracted for commercially made hard hats and issued them to every man on the project. The use of hard hats was encouraged, and deaths from falling objects were reduced.

Web archive of the Bureau of Reclamation website

On June 6, 1933, the first concrete was poured for the dam, a full 18 months ahead of schedule, but because of how concrete heats and expands the concrete couldn’t be poured in one continuous pour. Engineers determined that it would take 125 years for the concrete to cool, then it would most likely crack and crumble, collapsing the dam.

Instead, it was poured in squares with cooling rods inserted, with cool water and then ice-cold water streamed into the rods so the squares would set properly.

A popular myth that lives to this day is that several men were caught in accidents at the dam and entombed in the concrete. This is false. Each bucket of concrete, although delivered in 20 ton buckets, only filled the squares about one inch at a time.

Though no one is entombed in the dam, 112 deaths are associated with the building of the Hoover Dam. Amazingly the first and last death’s are related: the first death was a surveyor named J.G. Tierney; the last death was a young man who fell to his death named Patrick Tierney, J.G. Tierney’s son!

In the end, a total of 3.25 million cubic yards of concrete was used when the project was completed. More than 582 miles of cooling pipes were placed in the concrete.

All in all, enough concrete was used in the construction of the Hoover Dam to build a two-lane highway from San Francisco to New York.

The dam also created Lake Mead, a massive reservoir covering 28 million acres, with a surface area of nearly 250 square miles. Today Lake Mead National Recreation Area, the first and largest national recreation area in America, is home to camping, hiking and boating for nearly 10 million visitors each year.

From 1933-1947, the dam was called “Boulder Canyon Dam” or “Boulder Dam” interchangeably by the media and the public alike. Even though the 31st President of the United States, Herbert Hoover, was the spearhead in getting the dam approved and constructed, political warfare kept his name off the dam until 1947 when Congress passed a bill, fully restoring the name Hoover Dam.

The last concrete poured for Hoover Dam was on May 29, 1935 and it was dedicated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on September 30, 1935. It was formally handed over to the United States Government on March 1, 1936.

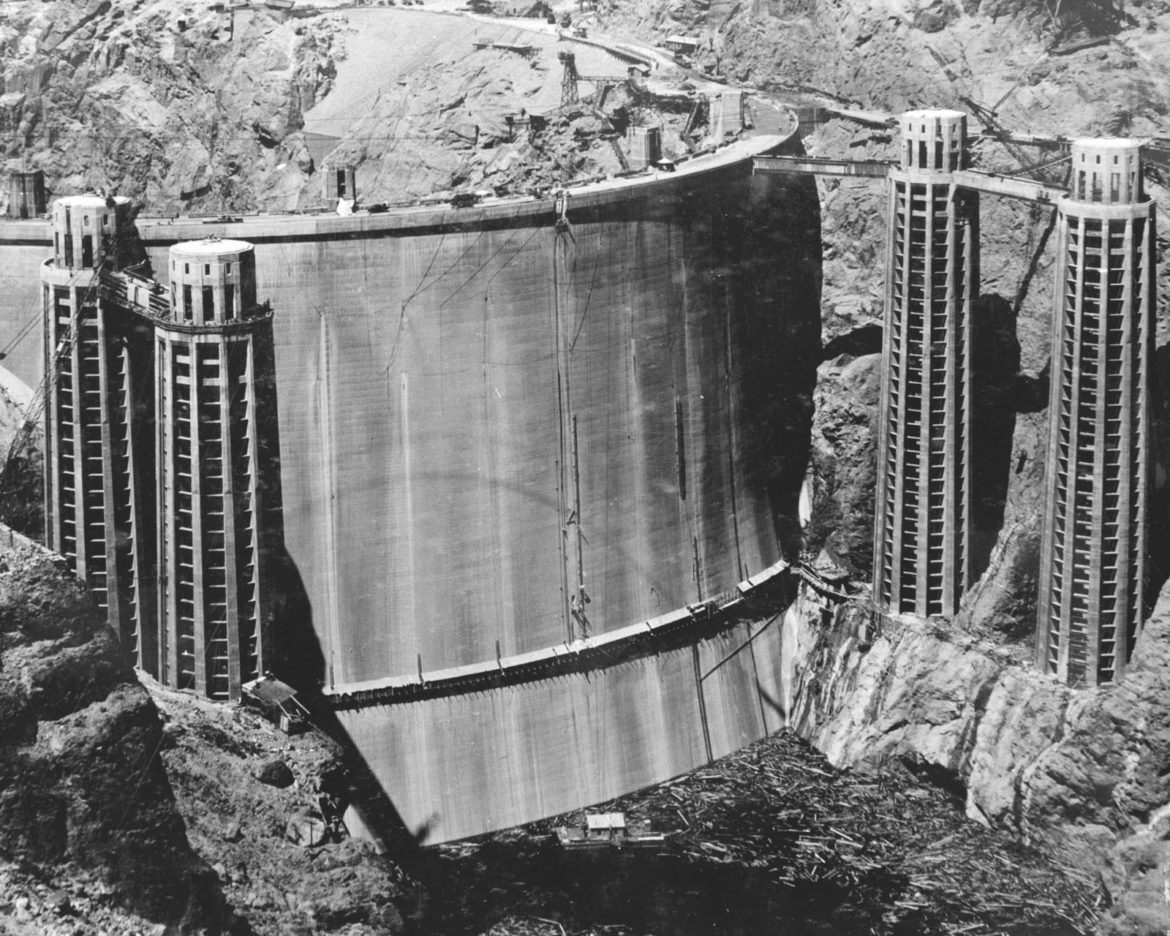

Hoover Dam stands 726.4 feet high, has a length of 1,244 feet, is 660 feet wide at its base, and 45 feet wide at its crest.

Although a Hoover Dam Bypass road has since been built, you can still drive atop the dam, passing from Nevada to Arizona while witnessing a truly breath taking view, no matter which window you gaze out from.

An innovate concept, one the world had never seen before, saddled with a staggering price tag in the middle of the Great Depression, constructed by a workforce of tough men, who braved the dangers to bring new life to a desolate part of our country, makes the Hoover Dam a true modern engineering marvel and one of the great wonders of America that needs to be seen to truly be believed.